Case Study: Bayesian Curve Fitting¶

In this case study, we use vegas to fit a straight line

to data with with outliers. We use the specialized

integrator PDFIntegrator with a non-Gaussian

probability density function (PDF) in a Bayesian

analysis. We look at two examples,

one with 4 parameters

and the other with 22 parameters.

This case study is adapted from an example by Jake Vanderplas

on his Python blog.

It is also discussed in the documentation for the lsqfit module.

The Problem¶

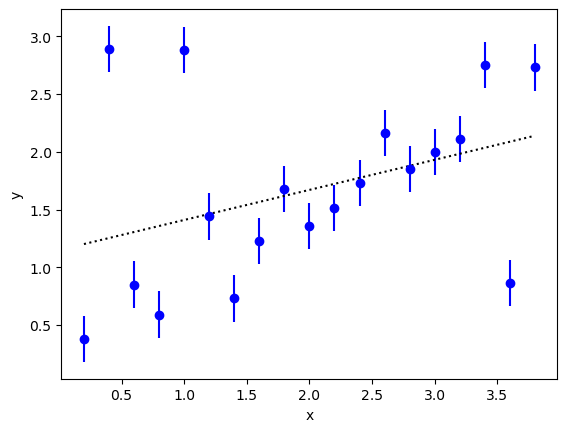

We want to extrapolate the y values in the following figure to x=0:

A linear least-squares fit to the data (dotted line) is unconvincing; in particular,

the extrapolated value at x=0 is larger than one while most of the data

near x=0 suggest an intercept less than 0.5. The problem, of course, is

caused by the outliers. There are at least three outliers.

A Solution¶

There are many ad hoc prescriptions for handling outliers. In the best

of situations one has an explanation for the outliers and can

model them accordingly. For example,

we might know that some fraction of the time our device

malfunctions, resulting in much larger measurement errors than usual.

This can be modeled in a Bayesian analysis by describing the

data using a linear

combination of two

Gaussian probability density functions (PDFs) for each data point.

One is the usual PDF proportional to

, where

the fit function

is

. The second is the same but

with the

for some

.

The relative weights assigned to

these two terms are

and

, respectively.

The following code does a Bayesian fit with this modified PDF:

import numpy as np

import gvar as gv

import vegas

def main():

# 1) create data

x = np.array([

0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.,

1.2, 1.4, 1.6, 1.8, 2.,

2.2, 2.4, 2.6, 2.8, 3.,

3.2, 3.4, 3.6, 3.8

])

y = gv.gvar([

'0.38(20)', '2.89(20)', '0.85(20)', '0.59(20)', '2.88(20)',

'1.44(20)', '0.73(20)', '1.23(20)', '1.68(20)', '1.36(20)',

'1.51(20)', '1.73(20)', '2.16(20)', '1.85(20)', '2.00(20)',

'2.11(20)', '2.75(20)', '0.86(20)', '2.73(20)'

])

# 2) create prior and modified PDF

prior = make_prior()

mod_pdf = ModifiedPDF(data=(x, y), fitfcn=fitfcn, prior=prior)

# 3) create integrator and adapt it to the modified PDF

expval = vegas.PDFIntegrator(prior, pdf=mod_pdf)

nitn = 10

nstrat = [10, 10, 2, 2]

warmup = expval(nstrat=nstrat, nitn=2*nitn)

# 4) evaluate statistics for g(p)

@vegas.rbatchintegrand

def g(p):

return {k:p[k] for k in ['c', 'b', 'w']}

results = expval.stats(g, nitn=nitn)

print(results.summary())

# 5) print out results

print('Bayesian fit results:')

for k in results:

print(f' {k} = {results[k]}')

if k == 'c':

# correlation matrix for c

print(

' corr_c =',

np.array2string(gv.evalcorr(results['c']), prefix=10 * ' ', precision=3),

)

# Bayes Factor

print('\n logBF =', np.log(results.pdfnorm))

def fitfcn(x, p):

c = p['c']

return c[0] + c[1] * x

def make_prior(w_shape=()):

prior = gv.BufferDict()

prior['c'] = gv.gvar(['0(5)', '0(5)'])

# uniform distributions for w and b

prior['gw(w)'] = gv.BufferDict.uniform('gw', 0., 1., shape=w_shape)

prior['gb(b)'] = gv.BufferDict.uniform('gb', 5., 20.)

return prior

@vegas.rbatchintegrand

class ModifiedPDF:

""" Modified PDF to account for measurement failure. """

def __init__(self, data, fitfcn, prior):

x, y = data

self.fitfcn = fitfcn

self.prior_pdf = gv.PDF(prior, mode='rbatch')

# add rbatch index

self.x = x[:, None]

self.ymean = gv.mean(y)[:, None]

self.yvar = gv.var(y)[:, None]

def __call__(self, p):

w = p['w']

b = p['b']

# modified PDF for data

fxp = self.fitfcn(self.x, p)

chi2 = (self.ymean - fxp) ** 2 / self.yvar

norm = np.sqrt(2 * np.pi * self.yvar)

y_pdf = np.exp(-chi2 / 2) / norm

yb_pdf = np.exp(-chi2 / (2 * b**2)) / (b * norm)

# product over PDFs for each y[i]

data_pdf = np.prod((1 - w) * y_pdf + w * yb_pdf, axis=0)

# multiply by prior PDF

return data_pdf * self.prior_pdf(p)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Here class ModifiedPDF implements the modified PDF. The parameters for

this distribution are the fit function coefficients c = p['c'], the

weight w = p['w'], and a breadth parameter p['b']. As usual the PDF for

the parameters (in __call__) is the product of a PDF for the data times a

PDF for the priors. The data PDF consists of the two Gaussian distributions

for each data point:

one, y_pdf, with the

nominal data errors and weight (1-w), and the other, yb_pdf,

with errors that are p['b']

times larger and weight w. The PDF for the prior is implemented

using gvar.PDF from the gvar module.

We want broad Gaussian priors for the fit function coefficients, but

uniform priors for the weight parameter () and breadth

parameter (

). An easy way to implement the uniform

priors for use by

vegas.PDFIntegrator is to replace the weight

and breadth parameters by new parameters p['gw(w)'] and p['gb(b)'],

respectively, that map the uniform distributions onto Gaussian

distributions (0 ± 1). Values for the weight p['w'] and breadth

p['b'] are then obtained from the new variables using the inverse map.

This strategy is easily implemented using a gvar.BufferDict

dictionary to describe the parameter prior.

The parameter priors are specified in make_prior() which returns the

BufferDict dictionary, with a Gaussian random variable

(a gvar.GVar) for each parameter.

The fit function coefficients

(prior['c']) have broad priors: 0 ± 5. The prior for

parameter p['gw(w)'] is specified by

prior['gw(w)'] = gv.BufferDict.uniform('gw', 0., 1.)

which assigns it a Gaussian prior (0 ± 1) while also instructing

any BufferDict dictionary p that includes a value for

p['gw(w)'] to automatically generate the corresponding value for the

weight p['w']. This makes the weight parameter

available automatically even though vegas.PDFIntegrator

integrates over p['gw(w)']. The same strategy is used

for the breadth parameter.

The Bayesian integrals are estimated using vegas.PDFIntegrator

expval, which is created from the prior and the modified PDF.

It is used to evaluate expectation values of arbitrary functions of the

fit variables. Here it optimizes the integration variables for integrals

of the prior’s PDF, but replaces that PDF with the modified PDF when

evaluating expectation values.

We first call expval with no function, to allow the integrator to adapt

to the modified PDF. We specify the number of stratifications for

each direction in parameter space, concentrating

stratifications in the

c[0] and c[1] directions (because we expect more structure there);

expval uses about 3000 integrand evaluations per iteration with

this stratification.

We next use the integrator’s PDFIntegrator.stats()

method to evaluate the expectation values, standard deviations and

correlations of

the functions of the fit parameters returned by g(p).

The output dictionary results

contains fit results (gvar.GVars) for each of the fit parameters.

Note that g(p) and mod_pdf(p) are both batch integrands, with the

batch index on the right (i.e., the last index). This significantly

reduces the time required for the integrations.

The results from this code are as follows:

itn integral average chi2/dof Q

-------------------------------------------------------

1 4.437(45)e-11 4.437(45)e-11 0.00 1.00

2 4.457(43)e-11 4.447(31)e-11 0.30 1.00

3 4.509(49)e-11 4.468(26)e-11 0.81 0.76

4 4.548(60)e-11 4.488(25)e-11 0.61 0.98

5 4.491(45)e-11 4.488(22)e-11 0.54 1.00

6 4.523(42)e-11 4.494(20)e-11 0.57 1.00

7 4.444(42)e-11 4.487(18)e-11 0.58 1.00

8 4.433(42)e-11 4.480(16)e-11 0.62 1.00

9 4.530(48)e-11 4.486(16)e-11 0.62 1.00

10 4.511(47)e-11 4.488(15)e-11 0.63 1.00

Bayesian fit results:

c = [0.29(14) 0.620(58)]

corr_c = [[ 1. -0.897]

[-0.897 1. ]]

b = 10.6(3.7)

w = 0.27(12)

logBF = -23.8270(33)

The table shows results for the normalization of the

modified PDF from each of the nitn=10 iterations of the vegas

algorithm used to estimate the integrals. The logarithm of the normalization

(logBF) is -23.8. This is the logarithm of the Bayes Factor (or Evidence)

for the fit. It

is much larger than the value -117.5 obtained from a least-squares fit (i.e.,

from the script above but with w=0 in the PDF). This means that the

data much prefer the

modified prior (by a factor of exp(-23.8 + 117.4) or about 1041).

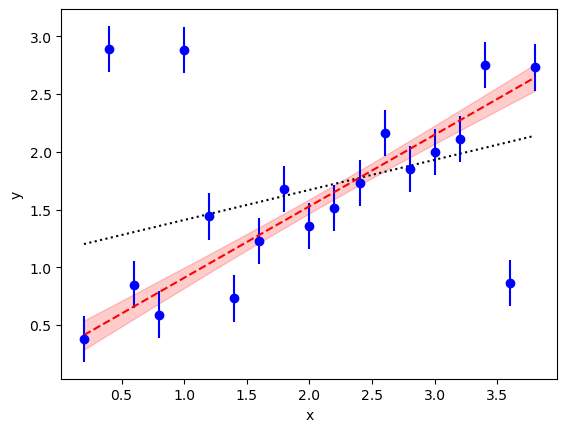

The new fit parameters are much more reasonable than the results from the least-squares fit. In particular the intercept is 0.29(14) which is much more plausible than the least-squares result (compare the dashed line in red with the dotted line):

The analysis also gives us an estimate for the failure rate w=0.27(12)

of our devices — they fail about a quarter of the time — and

shows that the y errors are b=10.6(3.7) times larger when

there is a failure.

Note, from the correlation matrix, that the intercept and slope are

anti-correlated, as one might guess for this fit. We can illustrate this

correlation and look for others by sampling the distribution associated

with the modified PDF and using the samples to create histograms and

contour plots of the distributions. The following code uses

vegas.PDFIntegrator.sample() to sample the distribution, and

the corner Python module to make the plots (requires the

the corner and arviz Python modules, which are not included

in vegas):

import corner

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def make_cornerplots(expval):

# sample the distribution and repack with the variables we want to analyze

wgts, all_samples = expval.sample(nbatch=50_000)

samples = dict(

c0=all_samples['c'][0], c1=all_samples['c'][1],

b=all_samples['b'], w=all_samples['w']

)

# corner plots

fig = corner.corner(

data=samples, weights=wgts, range=4*[0.99],

show_titles=True, quantiles=[0.16, 0.5, 0.84],

plot_datapoints=False, fill_contours=True,

contourf_kwargs=dict(cmap='Blues', colors=None),

)

plt.show()

The plots are created from approximately 50,000 random samples all_samples, which

is a dictionary where: all_samples['c'][d,i] are samples for parameters c[d]

where index d=0,1 labels directions in c-space and index i

labels the sample; and all_samples['w'][i] and all_samples['b'][i]

are the corresponding samples for parameters w and b, respectively. The

corresponding weight for this sample is wgts[i].

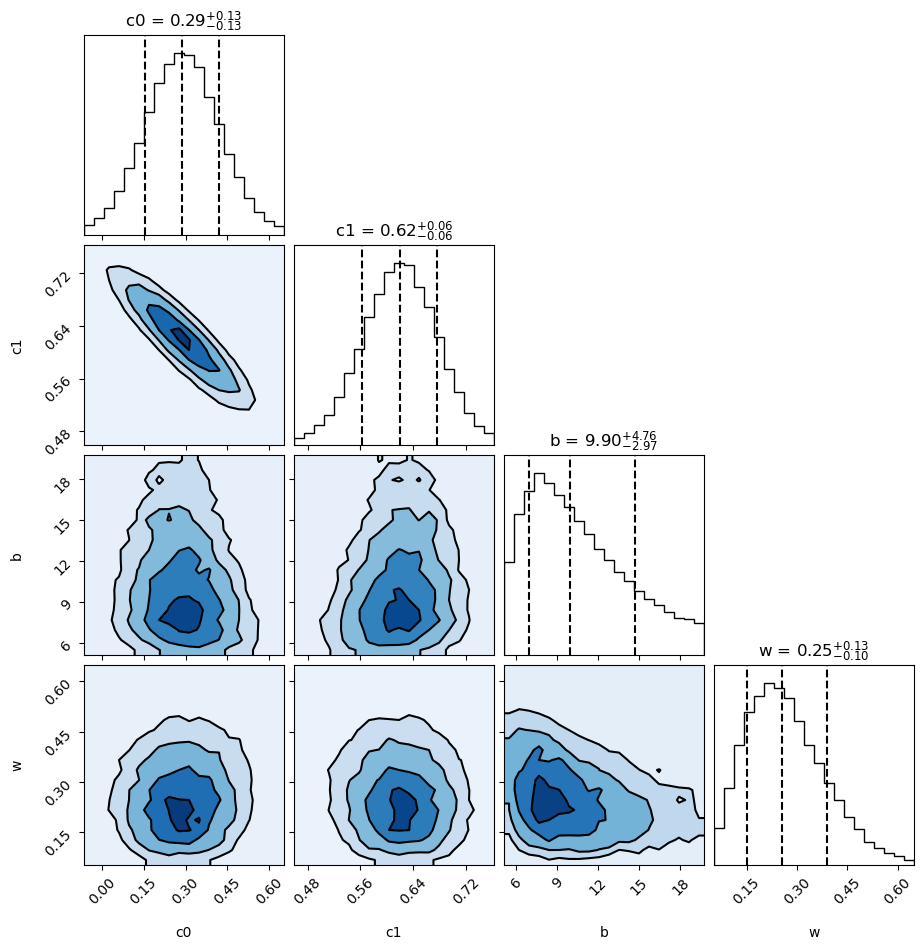

The output shows histograms of the probability density for each parameter, and contour plots for each pair of parameters:

From the plots, parameters c[0] and c[1] are reasonably Gaussian, with

a strong negative correlation, as expected. The other parameters are somewhat

skewed, but show only weak correlations. The contour

lines are at 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 sigma.

The histograms are labeled with the median values

of the parameters with plus/minus uncertainties that enclose 34% of the probability

on either side of the median (quantiles=[0.16, 0.5, 0.84]).

Finally, note that the Monte Carlo integrations can be made

twice as accurate (or faster) by using the results of a least-squares fit

in place of the

prior to define the vegas.PDFIntegrator. This is done, for

example, using the lsqfit module to replace

expval = vegas.PDFIntegrator(prior, pdf=mod_pdf)

by

fit = lsqfit.nonlinear_fit(data=(x,y), prior=prior, fcn=fitfcn)

expval = vegas.PDFIntegrator(fit.p, pdf=mod_pdf)

where fit.p are the best-fit values of the parameters from the fit.

The values of the expectation values are unchanged in the second

case but the optimized integration variables used by

vegas.PDFIntegrator are better suited to the

PDF.

A Variation¶

A somewhat different model for the data PDF assigns a separate value

w to each data point. The script above does this if

prior = make_prior()

is replaced by

prior = make_prior(w_shape=19)

and nstat is replaced by nstat = [20, 20] + 20 * [1].

The Bayesian integral then has 22 parameters, rather than the 4 parameters

before. The code still takes only seconds to run on a 2020 laptop.

The final results are quite similar to the other model:

itn integral average chi2/dof Q

-------------------------------------------------------

1 2.558(97)e-11 2.558(97)e-11 0.00 1.00

2 2.88(22)e-11 2.72(12)e-11 1.13 0.06

3 2.691(96)e-11 2.710(86)e-11 1.03 0.28

4 2.658(91)e-11 2.697(68)e-11 1.02 0.33

5 2.69(16)e-11 2.695(63)e-11 1.00 0.48

6 2.63(10)e-11 2.685(55)e-11 0.99 0.58

7 2.495(73)e-11 2.658(49)e-11 0.98 0.68

8 2.462(81)e-11 2.633(44)e-11 0.97 0.82

9 2.446(76)e-11 2.613(40)e-11 0.98 0.72

10 2.51(11)e-11 2.602(37)e-11 0.97 0.84

Bayesian fit results:

c = [0.31(17) 0.608(70)]

corr_c = [[ 1. -0.902]

[-0.902 1. ]]

b = 8.8(3.0)

w = [0.39(27) 0.66(23) 0.40(27) 0.40(27) 0.66(24) 0.49(29) 0.51(29) 0.37(26)

0.42(28) 0.39(27) 0.38(26) 0.37(26) 0.42(28) 0.39(27) 0.38(26) 0.39(27)

0.48(29) 0.66(24) 0.39(27)]

logBF = -24.372(14)

The logarithm of the Bayes Factor logBF is slightly lower for

this model than before. It is also less accurately determined (4x), because

22-parameter integrals are more difficult than 4-parameter

integrals. More precision can be obtained by increasing nstat, but

the current precision is more than adequate.

Only three of the w[i] values listed in the output are more than two

standard deviations away from zero. Not surprisingly, these correspond to

the unambiguous outliers. The fit function parameters are almost the same

as before.

The outliers in this case are pretty obvious; one is tempted to simply drop

them. It is clearly better, however, to understand why they have occurred and

to quantify the effect if possible, as above. Dropping outliers would be much

more difficult if they were, say, three times closer to the rest of the data.

The least-squares fit would still be poor (chi**2 per degree of freedom of

3) and its intercept a bit too high (0.6(1)). Using the modified PDF, on the

other hand, would give results very similar to what we obtained above: for

example, the intercept would be 0.35(17).